The New Jersey mayor with a plan to end traffic deaths (Bloomberg)

Shift into Safe News

In Hoboken, Mayor Ravi Bhalla has worked to redesign city intersections, install bike lanes and slow traffic. The result? Six-plus years of no pedestrian fatalities.

Before he was Hoboken’s mayor, Ravi Bhalla was just a local resident trying to cross the city’s main corridor with his two young kids. It was harder than it had to be.

“We simply had no pedestrian crossing signals. So I didn't know when the light would turn green on my side in order to cross safely with my child,” he recalled in a recent interview.

The stakes rose in 2015, when Bhalla — then a city council member — attended the funeral of an 89-year-old woman named Agnes Acerra. She had been killed crossing that same street. “It was completely unacceptable,” he said. "And I really felt that we needed to do a better job.”

Bhalla was elected mayor in 2017, and when he took office the next year, making Hoboken roads safer was an early priority. In 2019, he signed an executive order that kicked off the city’s commitment to Vision Zero — a campaign to end traffic deaths entirely in localities around the world. Hoboken took its vision even further, with goals to eliminate fatalities and injuries, all by 2030.

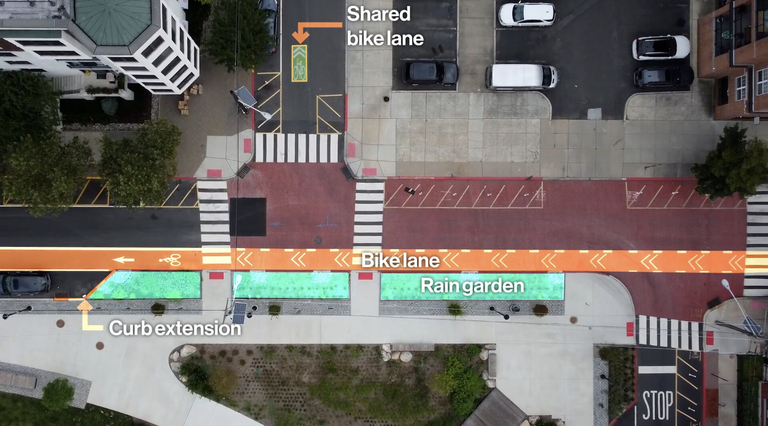

Armed with the Vision Zero plan, Hoboken has steadily been making incremental changes to its streets and transportation policies — with profound results. In 2021, Bhalla welcomed Citi Bike, which as of this summer has recorded more than 850,000 trips. In 2022, he lowered the citywide speed limit to 20 miles per hour (32 kilometers per hour). Crosswalks have been painted and repaved to increase their visibility, and more than 40 curb extensions have been installed to nudge cars farther from intersections. Today, nearly half of Hoboken's roads have bike lanes.

Hoboken’s traffic death problem wasn’t as serious as its neighbor across the river: Between 2014 and 2018, there were 4,500 crashes on Hoboken streets and three deaths, while more than 200 people were killed in each of those years in New York City. But the smaller community’s commitment to change is working. While pedestrian deaths in the U.S. reach 40-year highs, Hoboken hasn’t reported a single traffic death since January 2017, and injuries have dropped 41%. Still, it’s not yet 2030, and Bhalla isn’t declaring an early victory.

“It's an ambitious goal,” Bhalla acknowledges. "But we are aiming high and making progress."

CityLab sat down with the mayor in City Hall to discuss Hoboken’s transformation, the power of “daylighting” and the importance of setting ambitious community goals.

What are some of the first things you had to do from your position as mayor to start working toward a future with zero traffic deaths?

Community buy-in is so important. So we set up a Vision Zero task force, and that task force was meant to engage stakeholders, residents, engineers, public safety, to all come together and identify solutions that are innovative, that would advance the objectives of hope — making Hoboken a safer place to walk, bike, travel from one point to another. So that process took about two years to fully develop a Vision Zero plan. We started in 2019; it was fully developed by 2021. And then we went into the process of actually [implementing] some of the recommendations within our Vision Zero plan.

About that community buy-in: sometimes there is political pushback, or people who are resistant to change the way their city looks, feels and how they get around. What were the concerns that people had, and how did you deal with those?

Unfortunately, Hoboken, like many other cities, was designed in terms of its streets and roads for cars. And we're trying to change that. We're trying to make structural changes to that existing condition by making Hoboken a safer place to walk, to bike or to drive a vehicle. Change is not easy. And people are typically resistant to change. So we did face a number of roadblocks, so to speak. Among them, council members who did not want curb extensions, or bump outs at the intersections on Washington Street. I was actually even told in 2023 that a couple council members did not want these curb extensions to be placed in their wards, even though it would make it safer for their constituents to cross the street. But if you go through and implement the changes, I really think the evidence is there. You have to have political courage. We went ahead and made these changes, and we're already seeing appreciable improvements in public safety.

You've talked in the past about high impact, quick-build interventions. You mentioned the curb extensions. You're also working on signage, and paving and painting roads. From a high level, what’s the strategy of the infrastructure improvements? And then on the ground, what does it look like?

We try to use every single opportunity to avail ourselves of making and implementing Vision Zero improvements. So there could be something as simple as repaving a block in the city of Hoboken: When we repave that block, usually in the springtime, and do the routine things like road resurfacing, filling potholes, we kind of take a bird's eye view of that area and see what low-cost, high-impact measures we can implement in order to make that part of Hoboken a little bit safer. So just with a bucket of paint, you can actually create a curb extension; you can create high visibility crosswalks, which create a much safer environment at a very cheap cost. And then when you do the next iteration of repaving, you can really amplify and increase on those improvements that you've made. So this is change that is not happening within a day or a week. It's very incremental. But it's also very impactful.

Can you explain what curb extensions and daylighting are?

Sometimes people park on the corner of an intersection and that’s actually not legally permissible. Under the law, you need to park about 25 feet (8 meters) from the intersection. So a permissible parking spot has to be far enough away from an intersection so that a pedestrian and a car can see each other when there might be a street crossing, either by the car or the pedestrian. Essentially, daylighting removes that conflict created by a car at the corner of an intersection. And it does it in a number of different ways: You can do a bump out, which is physically creating an extension of the sidewalk in an aesthetically pleasing way. You can do a low-cost means, by putting a bike rack or bollards. Also, rain gardens are a form of daylighting, which serve a dual purpose of mitigating flooding as well as preventing pedestrian collisions.

Besides infrastructure, you’ve also enacted policy change.

We've implemented a program called Twenty is Plenty where the speed limit citywide is 20 miles an hour. Studies have shown that [the risk of killing or seriously injuring a pedestrian drops from 45% for a car going 30 mph to 5% at 20 mph]. If you decrease the speed limit from 30 miles an hour to 20 miles an hour, that's a major change. So we've implemented that. But within areas like parks and schools, we've reduced the speed limit even further to 15 miles an hour, because that's where you see the most children, vulnerable populations.

Can you talk about how state and federal leaders, or even peer localities, are helping in meeting these local goals?

Some of these borders, you could argue, are a little bit artificial. I point to the example of Jersey City [another Vision Zero success story]: A lot of people come to and from Jersey City on a regular basis. And we've been able to have a successful partnership with Jersey City, not just through the Citi Bike program, but through creating a protected bike lane that allows somebody to go from Hoboken to Jersey City, or from Jersey City to Hoboken in a safe manner. We're also working with the County of Hudson to get a protected bike lane at the 14th Street viaduct. And that, of course, takes collaboration and partnership with our friends at the county level.

I'm always interested to talk to mayors because your impact can be so great, but it's also term-limited. I'm wondering about how you think about the longevity of these goals that might or will post-date your time in office?

What we're trying to do while we have the opportunity to serve is create a foundation, create a new culture that will certainly outlast anyone's term in office. The idea behind Vision Zero is really changing the landscape, to make Hoboken a city that's more focused on people and specifically on pedestrians and bicyclists and different alternative modes of transportation, aside from vehicles. If we can change that culture, change that mentality, change the behaviors of residents, that will outlast any changes in administration and government. Progress might be implemented at the governmental level, but it really comes from the residents. Vision Zero was a very resident-driven process. And with time, we've successfully gotten buy-in from a large portion of the community.