Colorado weather may be the hardest in the world to predict

Meet CDOT’s head meteorologist Mike Chapman

By: Stacia Sellers, CDOT Strategic Communications Lead, Major Projects and Operations

Mike Chapman sits across from me at his desk at CDOT’s Traffic Operations Center in Golden, Colorado. Large computer monitors showing intricate weather forecast maps cast a glow across the room.

Chapman looks tired. He was up at 3:30 a.m., high atop Loveland Pass long before the sun rose. He was assisting a CDOT avalanche mitigation crew in starting one of the biggest avalanche slides he’s ever seen. One that, once at rest, left more than 20 feet of snow covering U.S. Highway 40. It’s all in a day’s work for Chapman, CDOT’s winter operations manager and the Department’s head meteorologist.

Colorado weather. The meteorology big leagues.

Colorado is the hardest place in the world to predict the weather. This is according to a man who has predicted weather across the globe: North Texas, Saudi Arabia, Mali, Senegal and more. Why? Because of the Rocky Mountains. And we’re all just along for the ride.

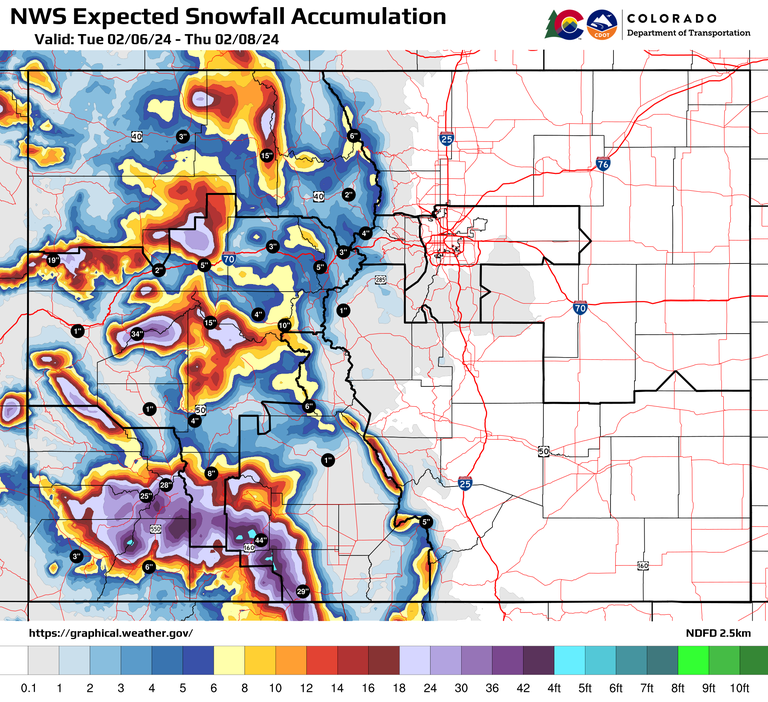

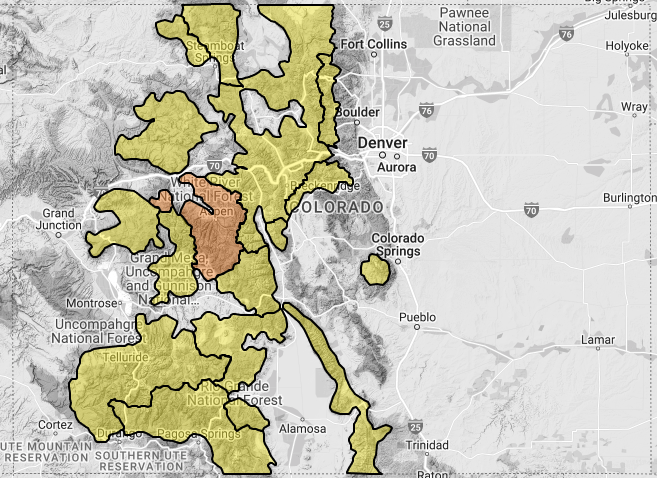

Colorado’s terrain plays a big part. Throw the Continental Divide in the middle of a flat state, and from a physics standpoint, says Chapman, it messes with the circulation of the atmosphere as it comes over the mountains. Weather systems intensify once they pass the highest peaks of the divide. Then, once those systems hit the Front Range, predictability is a pipe dream. The foothills to the west, Palmer Divide to the south and Cheyenne Ridge to the north are all geographic features that make modeling and forecasting a huge challenge.

High peaks, higher stakes

And then there’s the pressure. Pressure mounts depending on who’s relying on you to get it right. CDOT is the state’s largest agency with more than a billion dollars of annual funding and over 3,000 employees. The public depends on CDOT to keep roads open, safe and passable before, during and after severe weather. For every hour I-70 is closed (it’s one of our country’s most-traveled commercial thoroughfares), the state’s economy is impacted to the tune of $1.6million in economic value. And of greater value than that, the potential human cost. Simply put, the stakes are high.

The CDOT weather team is responsible for delivering accurate information to our operations teams in the field. Snowplow operators, for example, rely heavily on this information. They need to be in the right place at the right time. They need to know how much material to lay down on the road before a winter storm hits. If they’re not and they don’t, that could mean the difference between smooth sailing over Vail Pass or a 20-car pile-up that shuts down the interstate for hours.

However daunting the challenges may be, Chapman sees the weight of his role through a sporting lens: pressure is a privilege. His predictions are informed and there’s no bigger game than this.

The science of it all is breathtaking. So is the art.

For those who obsess over weather — backcountry skiers, snowmobilers, emergency responders and Broncos fans picking out their wardrobe for a November game at Mile High — “Our models are telling us …” is a phrase we hear again and again. But what does that mean?

The science and technology behind weather-predicting algorithms, or “models,” is staggering. There are many kinds of models. Models that cover the entire globe down to models that forecast through the crosshairs of a specific latitude and longitude.

The algorithms feed on data collected from weather balloons high up in the stratosphere down to ground level windspeed instruments like the one pictured below. Humidity, barometric pressure, jet stream shifts and ocean surface temperatures all play a role in who wins the bet on how buried Winter Park’s snow stake is going to be.

“It’s as much an art as it is a science,” said Chapman. Adding that you can only interpret weather models for so long — the models are many, and they don’t always agree. At some point, you just have to go with your gut.

Some of the brightest minds in our state using some of the most sophisticated software on the planet can flex as hard as they can, but ultimately … it’s one man’s best guess.

“Data and weather models only get you so far. As a meteorologist, knowing a place like Colorado, and building familiarity with its plains, peaks, valleys and canyons, will tell you more than what the weather radars and models show,” said Chapman.

Chapman’s Journey to Meteorological Mastery

It sounds like a dream job, but it wasn’t always his dream job. Chapman’s plan from a young age was to be a football player. Growing up in North Texas, breaking and making tackles was his life’s focus until a career-ending leg injury took him out of the game. Science stepped in and took its place. He stumbled into the field of meteorology in college.

“I grew up in a place that got pounded by weather,” he said. “And I loved it.”

With little clarity on his career path, he says he got lucky by ending up at Metropolitan State University in Denver studying under professor and mentor Tony Rockwood. Rockwood, a career meteorology professor and world-renowned expert in Colorado weather, sold Chapman on the idea of meteorology as a career.

It’s also good fortune that Boulder, Colorado employs one of the highest concentrations of meteorologists in the country. After graduation and before landing at CDOT, Chapman spent 15 years at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). He cut his teeth at NCAR and learned from some of the best in the business. It turned out he had a knack for it and a passion for the blend of science and nature. He later accepted a job at CDOT as its head meteorologist. John Lorme, director of the Division of Maintenance and Operations (DMO), understood that it was a much-needed role at the agency.

John Lorme, CDOT Director of the Division of Maintenance and Operation, emphasizes that CDOT’s needs for weather prediction are different than the needs of the general public.

“Most people may not know we need, and have, one of the best weather teams in the state,” Lorme said. “And we do. So much rides on staying one step ahead — and good decisions and recommendations about the weather matter to our crews and the public a lot more than many realize.”

The weather hits. Then what?

A unique aspect of Chapman’s current role its dynamism. He can spend days stoically staring at screens, geeking out on weather model maps and analyzing highly complex data. Then, a winter storm hits, and he quickly pivots – scrolling at light speed through his contact list to check the facts and learn what’s happening on the ground. People, after all, are the best gauge for how people are being affected by the weather.

Preparation is key, but Chapman says when the time is right and it’s necessary, he “raises the flag” and people jump into action. The day-of response is the most critical, he says. Things change on a dime and lives are often at stake.

Plows stop spreading sand and start pushing snow. CDOT teams at operations centers in the Eisenhower-Johnson Memorial Tunnels, Glenwood Canyon, Pueblo and Golden keep a close eye on traffic cameras to evaluate road conditions and monitor for traffic incidents…which skyrocket during heavy weather events. And CDOT’s Safety Patrol and Incident Response crews get twitchy with their gas pedals as they wait to be dispatched to help people who get stuck, or to clear a vehicle off the roadway so the rest of us can pass and be on our merry way.

The aftermath

After a severe winter storm has passed, what’s left? Snow. Lots and lots of snow. Avalanche danger is a big thing that the average motorist in Colorado doesn’t think about. Our state has more than 500 avalanche paths that threaten state highways. And when they go big, they can deposit more than 20 feet of snow on top of a mountain highway.

Leading CDOT’s avalanche control team is part of Chapman’s newly assumed role as manager of winter operations. Chapman and his team are responsible for triggering slides in the avalanche zones above Colorado highways at a time and in a way where nobody gets hurt, keeping roads closed for the shortest time possible. That’s often in the early morning hours long before the sun comes up.

Chapman isn’t the only man behind the curtain. He’ll be the first to admit it. He speaks with great fondness and respect about the men and women on his team. About the longstanding partnerships he and the department have cultivated — foremost of which is with the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC). The sister organizations have worked together for more than 30 years to monitor and mitigate the impact of avalanches and winter weather. The CDOT team also stays in close communication with the National Weather Service, NOAA and NCAR.

Don’t let perfection get in the way of progress

Colorado weather is complicated and unpredictable. Climate change is affecting our snowpack and weather patterns in a way we don’t fully understand. The number of Colorado residents and tourists who depend on a reliable and safe network of state highways continues to rapidly grow.

But Chapman and his team are up to the task. They may not always get it right, but it’s not for lack of effort or experience.

“We have a responsibility to get it right,” says Chapman. “And the buck stops with my team.”

Technology is improving, weather science is evolving, and there’s no shortage of talent at the agency.

“The biggest lesson I’ve learned is to be completely realistic and honest,” he said. “The most important thing we can do is get the best information we can to the people in the field — and the traveling public.”

So, enjoy the bright blue winter skies when we have them. The warm spring rains as they fall. And the gentle summer breeze on the Eastern Plains. But it is Colorado. There’s always a storm on the horizon — a fact of life that is not lost on the CDOT weather and winter operations team.

Read more stories about CDOT’s Division of Maintenance and Operations and learn about careers at CDOT here.

About the Author